Voodoo PR versus “Voodoo Academia”

This piece is one of my most-read blasts from the past. Its content remains vividly contemporary. Enjoy.

Richard Edelman’s Voodoo Academia replies to Professor Aneel Karnani of the University of Michigan’s Business School’s The Case Against Corporate Social Responsibility. But who’s voodooing whom?

Here’s the essence of Professor Karnani’s case:

Companies that simply do everything they can to boost profits will end up increasing social welfare. In circumstances in which profits and social welfare are in direct opposition, an appeal to corporate social responsibility will almost always be ineffective, because executives are unlikely to act voluntarily in the public interest and against shareholder interests.

Here’s the essence of Mr. Edelman’s reply:

[Edelman’s case studies] demonstrate that contrary to Karnani’s assertion, the decision isn’t whether to run an effective, “smart” business or a socially responsible, engaged one. Performance with purpose (a term used by PepsiCo CEO Indra Nooyi) is not an either/or proposition.

Now, as it happens, Richard Edelman makes a good point. But he also misses it completely. The core social purpose of a corporation is to provide whatever goods or services it is in business to deliver – be that street cleaning, cigarettes, incubators, medicines, machine guns or bubble gum. Mr Edelman, in contrast, believes that a smart business is an engaged one with a purpose. Engaged in what else other than what it does, I ask.

Mr. Edelman tries to explain it with three examples drawn from his client base:

Unilever’s Omo Detergent adopted the “Dirt is Good” campaign – aligning with the brand’s business proposition by asserting that “every child has the right” to be a child and get dirty. After fielding new academic research highlighting the importance of outside play for the physical and social development of children and engaging parents, governments and NGOs to take action, the campaign triggered real social change – Vietnamese schools agree to assess national provisions for school recess while the brand commits to build 100 playgrounds over three years.

He’s shooting himself in the foot. Unilever’s campaign has self-interest at its core. The aim here is to produce more dirty children that will require the use of more of its product to clean up the mess. Moreover, from my experience as a parent, kids don’t need much encouragement to get their clothes dirty or to play outside (try stopping them).

He tells us how the Clorox Brita’s FilterForGood campaign:

…inspires consumers – and communities – to take a personal pledge and even engage in (planet) healthy competition with others to reduce their bottled-water use, as well as informs them about other environmentally-friendly decisions that each can personally make.

In essence, he’s positioning his client’s “healthy product” against the bottled water industry’s and mains suppliers’ supposedly environmentally unfriendly or unhealthy alternatives. That is, for as long as Brita remains a client and come the day Edelman represents, say, San Pellegrino, or has to convince us that a utility produces a product fit to drink straight from the tap. This should warn us that the “public interest” Mr. Edelman favours is often just the selfish interests of his clients.

Then, if those two weak cases weren’t enough, he adds:

The Pepsi Refresh Project, partnering with NGOs and experts, is directly crowd sourcing ideas from consumers to foster innovation in social good – awarding more than $20 million this year to fund local community initiatives and ideas that refresh the world.

Regardless of the trendy crowd sourcing, that’s just a classic – old-style – brand marketing and awareness-raising campaign. It is, actually, a very low budget one for a company with $9.4 billion in revenues.

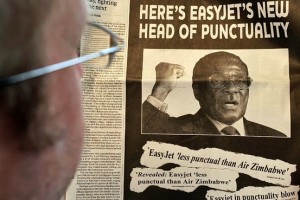

One wonders why Mr. Edelman didn’t mention another esteemed client: Ryan Air. It is one which is likely to accuse Professor Karnani of being soft rather than harsh in his defence of profit. Ryan Air states unambiguously that shareholder value comes before its staff, customers, partners and suppliers. Ryan Air has little time for stakeholder PR or for CSR, except as the butt of jokes. Here’s the brief that Edelman pitched for:

Wanted: PR firm who is able to LOL at the advertising gags, and doesn’t mind poking fun at expensive airports, rivals, prime ministers … and even popes! No precious, sensitive, politically correct or clock-watching publicists need apply. Long hours, stamina and patience of St. Christopher, the patron saint of travel, are all prequisites.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I’m not against corporations acting responsibly or managing their risks properly. I accept Ryan Air is an outlier; though it is one which has moved an entire industry’s behaviour in its direction. It is just that most CSR is shallow dishonest nonsense that sails close to propaganda, as BP’s Beyond Petroleum clearly did.

It is precisely such transparent charades and double-speak that generates the disabling cynicism that undermines public confidence in modern institutions. So there’s something refreshing about Professor Karnani’s bluntness and Ryan Air’s Michael O’Leary’s loud mouth.

Of course, in one sense there’s a bit of voodoo coming from both Mr. Edelman and Professor Karnani. The problem with deciding between profit-first or profit-with-purpose is that they are difficult to separate. Firms live within society and have all kinds of unavoidable obligations to fulfill as they produce profit.

One has to ask some tough questions about Mr. Edelman’s motivation, however. His main concern seems not to be the public good as much as helping firms restore their credibility and by so doing avoid state interference in their affairs. He says:

We are at a very important moment in the relationship between business and society. The catastrophic economic events of September 2008 undermined the confidence in the private sector’s ability to self-regulate. Bankruptcies of centerpiece companies in the global economy, such as GM, plus reputation issues for leaders in finance (Goldman Sachs), energy (BP) and transport (Toyota) have called into question the values of corporate leaders. In the race for public credibility, it is fortunate for business that its prime regulator, government, is not seen as a worthy replacement as the leader in the dance.

My beef is not with what Mr. Edelman wants to achieve; a free and mostly self-regulated market place. It is with how he believes that he can win public acceptance for it. I rebel, as do most people who are moderately sceptical of corporate humbug, to his pandering to the more infantile elements of this discussion; you know, the audience who cannot (supposedly) be told the truth because it would destroy their illusions.

So, I’d like to leave you with what I think is an effective demolition of Mr. Edelman’s style of PR, by quoting Professor Karnani’s robust expose of it:

Executives are hired to maximize profits; that is their responsibility to their company’s shareholders. Even if executives wanted to forgo some profit to benefit society, they could expect to lose their jobs if they tried—and be replaced by managers who would restore profit as the top priority. The movement for corporate social responsibility is in direct opposition, in such cases, to the movement for better corporate governance, which demands that managers fulfill their fiduciary duty to act in the shareholders’ interest or be relieved of their responsibilities. That’s one reason so many companies talk a great deal about social responsibility but do nothing—a tactic known as greenwashing.

Exactly!

Note; this was first published in August, 2010

In some ways I think that Edelman seems closer to Professor Karnani than we might think since his examples of CSR are primarily about boosting the bottom line of the organisations. The social benefit, where it occurs, seems to be a tangential output of a campaign that primarily is about the organisation’s income. That’s enlightened-self interest, which may be a perfectly valid reason to undertake CSR initiatives – one that is acceptable to shareholders and hence within the good governance rules.

However, I am not convinced that these publicity-related examples are the type of CSR that organisations should be encouraged to focus on as good corporate governance. For me, those are the integral aspects of running the business – that relate to environmental performance, treatment of employees and so forth. And, yes, these are areas that are also enforced by legislative controls. Of course, that means the pursuit of profit as a primary motive means corporates may seek out less restrictive environments in which to operate – and maybe their stakeholders don’t care if the price of child labour produced goods for example is cheap enough.

So the argument about responsibility being all about (short-term) profit doesn’t totally work either if the focus is on meeting the minimum standards that an organisation can find somewhere in the world.

Does that mean that an organisation cannot be successful if it puts ethical concerns at the heart and centre of its business – not engaging in publicity-oriented gimmicks or just meeting minimum standards?

My argument relating to Toyota in particular (from personal knowledge of the company) is that its recent reputational – and financial – problems started by a shift away from being value driven by quality and other responsibilities. It may well have been responding to needs for short-term profit or market share – but at a longer-term consequence.

So I think there can be social responsibility that is enlightened self-interest and of value to the public – but that means not just looking at cutting corners today for quick profit and also avoiding the publicity-oriented type of CSR initiative that is really just cause related marketing.

It’s a good debate – brilliantly summarised by you above – but it’s really not new. In the blue corner, there’s Milton Friedman arguing that the sole purpose of private business is profit. In the red corner, there’s David Cameron’s adviser Steve Hilton (leading a crowd of others) arguing that ‘good business’ is responsible – as well as profitable.

I’m surprised how many PR textbooks present CSR as something new (it isn’t) – and as the ultimate vindication of PR (or an ethical defence of PR).

Perhaps (as I often seem to comment here) there’s a difference between the US and Europe. Friedmanite capitalism has been the norm in the US whereas during the Thatcher years is was seen as a novelty in Europe.

To summarise, perhaps the US views corporate responsibility as new and exotic whereas Europe views Chicago School capitalism as a foreign import.

I think Paul Seaman is mostly right. Firms are in some sense citizens just as their employees and customers are. They have to be corporately decent. Some want to be a positive force for good in ways which aren’t directly aligned to their commercial interest, and that’s OK too, if their owners like the idea.

But the heart of Paul’s argument is a plea for honesty. If a firm acts in a social way because that will bring profit (now or in the future) then it needs to say that its primary interest is profit.

The big gamble firms and PRs must take is this. Are the public infantile? Are they incapable of seeing that firms almost always do the bit of good which suits them? Isn’t that what the Edelman cases tell us? And shouldn’t we hang on to the adult idea that virtue consists in sacrifice? Can firms “do” sacrifice? Should they? Are they that sort of entity?

Indeed, the point of Paul’s argument seems to me to be that because firms are not persons, they have to ask themselves what they owe the public as institutions. I would say frankness is high on that list and that honesty as to motivation makes a very good beginning. We can leave self-deception or humbug to individual persons, of whom we expect less (not more) than firms.

The professor obviously has read Ayn Rand, probably both “The Virtue of Selfishness” and “Atlas Shrugged.”

Excellent post, Paul, thanks for the great summary.

I think you’re probably right about Edelman’s excesses; that’s almost an occupational hazard in PR, where the temptation to change the message, rather than the facts, is endemic.

But the real ‘right’ ones here, I’d suggest, are professors Bishop and Khurana, whom Edelman (to his credit) sought out and quoted. Their quotes speak better, I think, than the ones you selected from Edelman himself, which were arguably chosen with some self-serving flavor.

Bishop: “Markets and their relation to public interests are constantly evolving – and the actions of companies play a crucial role in whether they evolve in a direction that serves the public interest.”

Bishop: “How can you win the battle for talent in a world where workers are increasingly choosy about the ethics and mission of the firm they work for?” He argues passionately that smart companies are focused on long term shareholder value, not short term earnings. “The current economic crisis was caused not least by endemic short-termism in capitalism.”

Khurani: “…the Karnani model “has no application to the rest of the world, beyond a mile square radius from the University of Chicago campus that housed Milton Friedman. In Europe or in China or in India, a company would not have the license to operate this way.” He added that there “is a group of persistent rationalizers who change the facts instead of changing their theory, offering old wine not even in new bottles.”

Khurani: “In addition to economic performance as determined by economic outcomes, organizational decisions are also judged by the criteria of legitimacy…A legitimate organization is one that is perceived as pursuing social acceptable goals in a socially acceptable manner….in some cases the social logic of values is linked to an economic logic of resource maximization, but in other cases these can be in tension, which means that effective societal outcomes cannot be left to the invisible hand of unregulated or unguided markets.”