Chernobyl book review: Manual for Survival: A Chernobyl Guide to the Future by Kate Brown

Allen Lane imprint Penguin Books 2019

ISBN-13: 978-0393652512

The shocking truth about Chernobyl is how few people were killed or made ill by radiation.

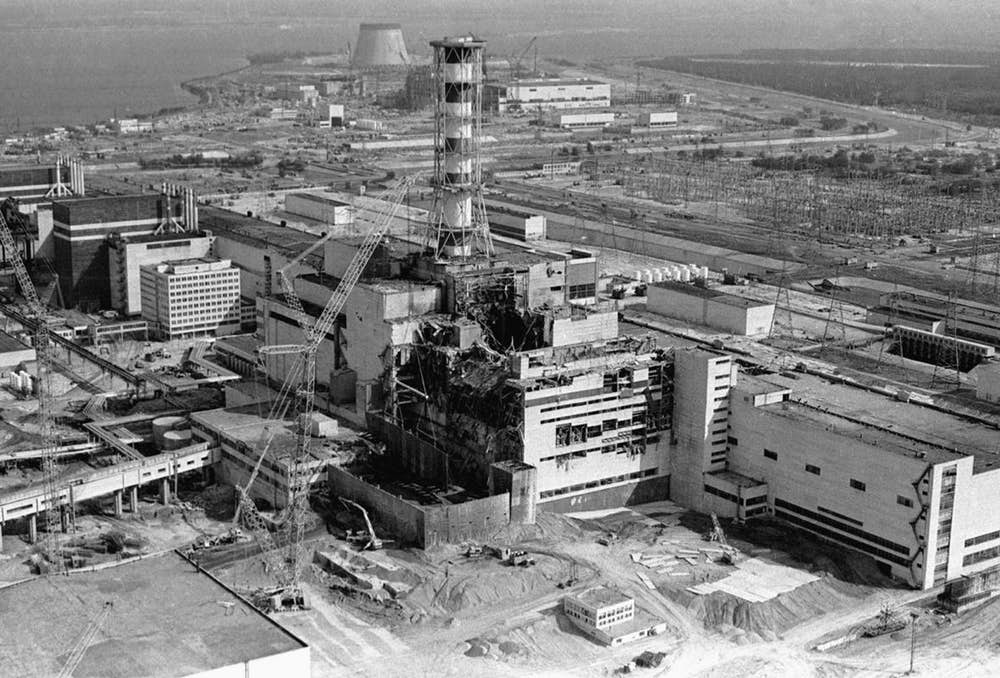

I’m getting an adrenaline rush watching HBO and Sky TV’s five-part dramatisation of the Chernobyl accident, because in 1995 I spent six months working at the heart of the disaster. At that time, I was the only Westerner permanently based at the site. So I’m pleased that – so far – the Chernobyl drama has delivered a riveting portrayal of blundering bureaucrats and their betrayal of plant operators. It stirs my heart to see proper credit given to those involved in the heroic effort to contain the accident and clean up the mess. The scale of the fallout, which displaced hundreds of thousands of people, affecting millions living in designated contamination zones, was massive. The response to it was courageous and inspirational.

Nevertheless, there was in 1986 an inexcusable criminal cover-up by the Soviet authorities led by Mikhail Gorbachev. Undoubtedly, there was an initial hesitation in the West to criticise Gorbachev, who they were courting. There was also a misguided attempt to retain public confidence in nuclear energy at home, which made our masters slow to expose the magnitude of what had occurred. This global downplaying of the scale, causes and consequences of the accident generated mass angst and a loss of trust in the West and East alike. The cost of that cover-up put the last nail in the Soviet Union’s coffin; sealing its fate in the cemetery of history. The accident, around one hundred kilometers from Kiev, fuelled Ukrainian nationalism and sparked the creation of Ukraine as an independent state. There’s no doubt that, following on from Three Mile Island in 1979, Chernobyl was a hammer blow to the global atomic industry. Not least because the industry had repeatedly claimed that such an accident – a full nuclear core meltdown and an explosive release of a reactor core to atmosphere – could never happen.

So it is difficult to criticise broadcasters in the entertainment business for creating an exciting, authentic-looking historical drama. But having said that, we cannot be so charitable toward Kate Brown’s new book Manual for Survival: a Chernobyl Guide to the Future.

Brown is Professor of Science, Technology and Society at MIT, who specializes in environmental and nuclear history and the Soviet Union. Brown’s ominous-sounding Manual for Survival sets out to do two things. First, she wants to expose how the official narrative of Chernobyl was written by the United Nations as part of a thirty-three-year cover-up, in cahoots with the KGB and Western intelligence agents. This, she argues, was designed to downplay the horrendous health consequences of what happened at Chernobyl to protect the reputation of the Soviet Union and Western interests from lawsuits arising from the testing of nuclear weapons in the Cold War. The second main point of her book is to explain the “Grand Canyon-sized gap between the UN and Greenpeace estimates of fatalities”, so that we can come to a more certain number. But Brown fails to justify either of her book’s core objectives.

Brown’s depiction of the cover-up gets bogged down in a conspiracy theory. She asks us to believe that the KGB and Ukraine’s SBU, the UN and Western governments and Soviet and post-Soviet satellite regimes had common interests over three decades. Furthermore, Brown’s attempt to provide more accurate death tolls relies on hearsay. Yet Manual for Survival attacks relentlessly the credibility of a body of evidence that is well researched and which has stood the test of time.

The UN estimates of fatalities were first published in 2005 in the landmark Chernobyl Forum Report. Its research and publication was led by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) on behalf of – and endorsed by – eight UN agencies, including the World Health Organisation and Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the governments of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine. The report assessed all the epidemiological evidence in a collaborative effort involving hundreds of experts. It found that there had been fewer than 50 deaths (today that stands at 54) directly attributable to radiation from the disaster; almost all being highly exposed rescue workers; many who died within months of the accident but others who died as late as 2004.

In response Greenpeace, as Brown says, stated that 200 000 people had already died and that there would be 93,000 fatal cancers in the future, compared to the UN’s estimate of between 2,000 and 9,000. Though in 2006, Greenpeace International was telling journalists that 500,000 people had already died as a consequence of the accident.[1] And it was saying that in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine, 200,000 of these deaths had occurred between 1990 and 2004. But Brown mentions neither of these claims.[2]

Decades after Chernobyl exploded, Brown maintains that there is still a need for a large-scale, long-term epidemiological study of the consequences of the impact of low-level radiation on human health in the affected areas. That may be so. But this does not validate her main argument. Dismissing the Chernobyl Forum Report’s conclusions, she says that the “study never came together. Why?”.

She also wants us to believe that after Fukushima blew its top in 2011, scientists told the public that they had no certain knowledge of the effects of low-dose exposures to radiation on human beings. Yet she provides no evidence of them claiming ignorance on this subject, which is well understood by experts. She opines that because of our failure to learn the lessons of Chernobyl, we are stuck in an “eternal video loop”, with same scene playing over and over again from Three Mile Island and Chernobyl to Fukushima. So she says that after Fukushima, Japan’s scientists began behaving as if they were in the USSR, because they:

Did not recognize they were reproducing the playbook of Soviet officials twenty-five years before them. And that leads to the pivotal question: Why after Chernobyl, do societies carry on much as before Chernobyl? [page 3]

It is as if Brown lives in a world different to the rest of us. One in which Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and USA carried on believing in the merits of nuclear energy in the wake of Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and Fukushima. The real video-loop has been mass panics about the supposed unknown impact of low-level radiation. So the question she might have asked is whether the Japanese response to Fukushima is a case study highlighting the overly precautious creation of an exclusion zone. Reassuringly, the nearby town of Okuma has since been declared safe for residents to return. And Professor Geraldine Thomas of Imperial College – one of Britain’s leading researchers on the effects of radiation on the human body – says:

The radiation [at Fukushima] has not been the disaster. It’s our response to the radiation, our fear that we’ve projected on to others, to say this is really dangerous. It isn’t really dangerous and there are plenty of places in the world where you would live with background radiation of at least this level.[3]

One of Brown’s core case studies is the genuine – job-risking – struggle fought by people such as Keith Baverstock at the WHO. He was one of group of courageous scientists and doctors who battled to convince their employers of the unexpected outbreak of thyroid cancers among children. They discovered, and made sure it was widely known, that radioactive iodine (iodine-131 and caesium 137) was more carcinogenic than had been supposed. But while Brown tells quite well their commitment to follow the evidence, she seems not to recognise the significance of the fact that the likes of Baverstock won their battle. She fails to fully acknowledge that the final Chernobyl Forum report of 2005 incorporated their findings. And she never tells us that it was Baverstock himself who kept telling the media (including me) that the biggest cause of health problems among people living in affected territories was increased anxiety and stress levels fanned by scaremongers.

Brown omits to tell her readers what happened to Baverstock’s critique of the Chernobyl Forum after he left WHO. So I shall summarise it here because it is the most considered interrogation of the Chernobyl Forum findings that I have read.

Along with his colleague Dillwyn Williams, Baverstock has criticised the conflicted politics behind the Chernobyl Forum and its impact on its research. He has pointed out the limits of the existing body of knowledge and called for more intensive research into the long-term effects of Chernobyl. He has also highlighted the tendency of the IAEA to always cite the lower figure of harm when higher ones could equally be given (too often they omit to say there could be up to 9000 deaths). He correctly says that we won’t know for sure the full outcome on human health for decades. Even then the real toll might still be lost in background deaths and sickness – including novel kinds – because low level radiation impacts are difficult to detect.

But while Baverstock has advanced criticisms and scepticism – not least with regards to overly reassuring messages – he has never endorsed Greenpeace or Brown-type speculative inflation of the evidence, or Brown’s meta-narrative conspiracy theories. All that sounds reasonable to me.[4

In contrast, Brown misrepresents much of what was uncovered by scientists investigating the state of children’s health. She does so in order to back her claim that the Chernobyl exclusion zones will have to remain abandoned for much longer than anybody ever expected; when actually they are being repopulated gradually in 2019. In her final chapter – Berry picking into the future – she unwittingly exposes her ignorance:

Biologists first predicted the ecological half-life of caesium would be fifteen years. Now, for reasons they do not fully understand, researchers from the U.S. Department of Energy estimate that period for half of cesium-137 to disappear from Chernobyl forests will be between 180 and 320 years. [page 302]

She’s suggesting here that scientists learned something new about the properties of caesium-137. But we know for sure that the half-life of caesium is 30 years. So I checked out the source she provided. It led to an article in Wired – from 2009 –titled Chernobyl exclusion zone radioactive longer than expected by Alex Madrigal. [5]

What the article actually says is that, for reasons scientists don’t yet grasp, caesium-137 is seemingly being replenished in parts of the disaster zone. As the article says, this could delay the time it takes to repopulate parts of the exclusion zone. Interestingly, there is no mention in the article of caesium-137 ever having an expected ecological half-life of 15 years, as reported by Brown. And contradicting her claim that long-term scrutiny of the contaminated zone has not been intense, the article reports how scientists in the U.S. have spent more than 20 years, “providing a unique experiment in the long-term environmental repercussions of a near worst-case nuclear accident”. Though at the bottom of the article there’s postscript, which could explain why the entire article led Brown into trouble:

The second paragraph of this story was updated after discussion with Tim Jannik [nuclear scientist at Savannah River National Laboratory] to more accurately reflect the idea of ecological half-life. [Ibid]

The point is that Brown is basing her conclusions on secondary sources, written by people who clearly failed to understand what the scientists who briefed them said. Moreover, Brown clearly does not know enough about nuclear physics to spot something that is plainly in error. But she does have the confidence to imply that U.S. Department of Energy backs her opinion. Meanwhile in the real world, according to Prof Jim Smith from the UK’s University of Portsmouth, while the Chernobyl exclusion zone is contaminated, “if we would put it on a map of radiation dose worldwide – only the small ‘hotspots’ would stand out”[6].

In her concluding chapter, Brown tells us what she considers to be a more credible estimate of the total number of fatalities – so far – that have resulted from the Chernobyl accident. And once again we gain an insight into the lack of any real evidence or credible sources for forming her opinion:

Off the record, a scientist at the Kyiv All Union- Center for Radiation medicine put the number of fatalities at 150,000 in Ukraine alone. An official at the Chernobyl plant gave the same number. That range of 35,000 to 150,000 Chernobyl fatalities – not 54 – is the minimum.

If her unnamed sources were communicating facts, there is no doubt that this would show up as a significant and easily measurable statistic. If even half or one third of those deaths actually occurred, they would be transparent in the statistics and impossible to hide in reality. The fact is that the affected area in Ukraine – where the fallout fell – has a population of around two million. Yet, according to official statistics quoted in the Chernobyl Forum report, there’s been no increase in the normal background rate of deaths, cancers and birth defects. That remains true today, according to Ukraine and other investigators. Her guesstimates of numbers, it appears, were plucked from the air and given no common sense attention to calibrate their credibility.

I recommend the TV drama Chernobyl because nobody expects it to be totally factual and because it has done a very good job – so far – of humanising the world’s worst industrial disaster. But this scaremongering book by Kate Brown – designed to stop nuclear power progressing – should be put in the dustbin along with the Soviet Union.

[1] UN accused of ignoring 500,000 Chernobyl deaths https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2006/mar/25/energy.ukraine

[2] https://www.sortirdunucleaire.org/IMG/pdf/greenpeace-2006-the_chernobyl_catastrophe-consequences_on_human_health.pdf

[3] Is Fukushima’s exclusion zone doing more harm than radiation? https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-35761136

[4] The Chernobyl Accident 20 Years On: An Assessment of the Health Consequences and the International Response https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1570049/

[5] https://www.wired.com/2009/12/chernobyl-soil/

Excellent and thoughtful piece, Paul. It is a subject where you have unique experience. I guess we have to accept that there is money in shocking people and many will believe what they watch on TV. As for the book, there are plaudits to be gained from scaring people with exaggerated numbers of deaths, righteous expressions of public concern and shouts of “cover up”. It has been done many times before. Thank you for exposing another example!

Misleading title, since you mean how few people died at the time of the explosion not the predicted 9000 from the UN estimates.

Alex, the UN does not predict 9,000 deaths. It says there may be up to 9,000 at the most extreme limit. So far there are 54 known deaths attributable to the accident. Meanwhile, risks are declining.

Risks are declining of course but where is the long term figure? Cancer rates in Belorussia for instance need to be looked at, difficult of course but to say only 54 died stretches credulity.

Cancer rates and general health in all the affected areas and among all the affected populations have been examined and continue to be monitored. No increase in cancers, abnormalities or the death rate has been recorded. Sometimes the truth is shocking.